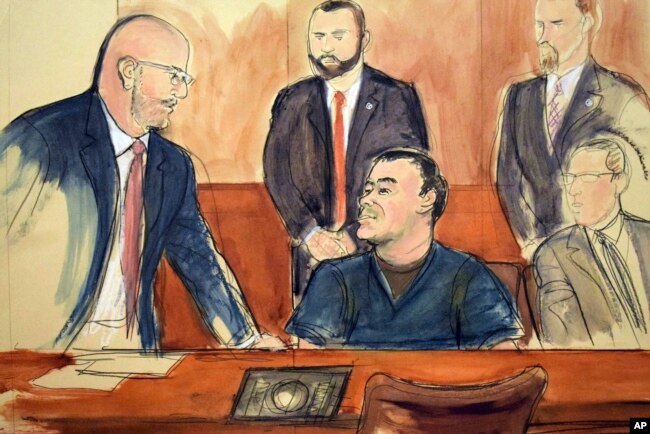

Claims of jury misconduct in the trial of drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman have drawn new attention to the digital-age challenge courts face in preventing jurors from scouring media accounts or conducting their own research before rendering a verdict. It’s a phenomenon that has been called the “Googling juror”, VOA news reports.

“Everyone has the world at his fingertips,” said Guzman attorney Jeffrey Lichtman. “Twenty years ago, you didn’t have to worry about that.”

Lichtman told The Associated Press on Thursday that there are now serious questions surrounding Guzman’s conviction this month on drug-smuggling and conspiracy charges, and that he plans to ask U.S. District Judge Brian Cogan to bring in all 12 jurors and six alternates to question them about reports that several flouted admonitions to avoid media accounts of the case.

One juror anonymously told VICE News this week that at least five members of the panel had followed media reports and Twitter feeds during the three-month-long trial and were aware of explosive — and potentially prejudicial — material that had been excluded from the proceedings.

“It’s clear we have to get them back into court and get some answers about some massive misconduct,” Lichtman said.

The U.S. attorney’s office in Brooklyn declined to comment Thursday.

New trial?

In some cases, similar jury shenanigans have been deemed prejudicial enough to warrant a new trial, a possibility experts say can’t be ruled out in Guzman’s case.

“This is a question about fundamental fairness,” said former federal prosecutor Duncan Levin. “It’s presumptively prejudicial for a juror to have this information, and it’s a step more outrageous for them to have accessed it when the judge specifically told them not to.”

Shy of sequestering jurors, stripping them of their electronics and repeatedly warning them, judges are limited in the steps they can take to prevent outside sources of information from infecting deliberations.

“The jury system depends on people being honest in what they say and what they do,” said Rock Harmon, a former prosecutor in Alameda County, Calif. “There’s just no way to prevent this except to stress what they need to do.”

In Guzman’s case, the anonymous jurors were not sequestered but were escorted by U.S. marshals to court, where they were required to give up their phones. They were allowed access to their devices at any other time, though the judge gave them a standard instruction each day not to view news or social media about the case.

Still, the juror who spoke with VICE News said five jurors involved in the deliberations and two alternates had heard about child rape allegations that had been made against Guzman and covered by the news media but not admitted into the trial. The juror also described an instance in which a juror used a smartwatch to look up a news story just moments after Cogan met with them privately to ask them whether they had been exposed to any recent media coverage.

“This is a growing phenomenon, and courts are struggling with how to address it,” said Thaddeus Hoffmeister, a University of Dayton law professor whose research has focused on juries. “You’re dealing with people today who have more faith in Google than the witnesses being called to testify.”

Uphold oath or pay the price

The best remedy, Levin said, is for jurors to uphold their oath or face repercussions. In Guzman’s case, he said, if they acknowledge having disregarded Cogan’s instructions, they should be held in contempt of court.

But convincing Cogan that the misconduct was real and that it is enough to order a new trial is a long shot, said former federal prosecutor Michael J. Stern.

“The judge will have to decide whether there was a reasonable possibility that the information could have affected the jury’s verdict,” Stein said.

Either way, Lichtman said, the revelations surrounding the panel that convicted his client are “sad and distressing.”

Guzman, who is facing a mandatory life sentence, “is going to die in jail,” he said. “That’s why I repeatedly asked the jury to just give him a fair trial. It turns out that was too much to ask.”