Sectarian tensions are rising in Northern Ireland — and not only because of Brexit and the possibility that the island of Ireland will once again be divided by a so-called “hard border”, VOA news reports.

The province is also on edge about whether former British paratroopers will face trial for the deaths of 14 unarmed protesters, who were shot 47 years ago in a massacre that became known as Bloody Sunday.

Prosecutors are expected to make their decision public next week, but the signs are that several of the ex-paratroopers, now in their 70s, are more likely to face murder charges for their roles in the shootings in 1972 than previously thought.

Justice campaigners have told the British media that they know soldiers will face prosecutions for the killings. Some of the army veterans themselves have said they expect to be charged.

Whatever the decision by the prosecutors, which comes after a seven-year police inquiry, it is bound to cause a political storm. The province’s Irish nationalist mainly-Catholic minority will be furious if there are no prosecutions; while pro-British mainly-Protestant Unionists are already up in arms at the very idea that the army veterans could stand trial.

The families of the dead will be told of the decision on March 14, the day after the British parliament votes on whether to leave the European Union, and if so how. That vote, already a source of mounting sectarian anxiety in the British-run province, could determine whether border checks are reinstated on the frontier separating the six counties of Northern Ireland from the 26 counties of the Irish Republic.

On Tuesday, the head of Northern Ireland’s civil service warned of risks in the event of a no-deal Brexit and the reimposition of customs and immigration checks along the border. In a letter to the province’s main political parties in Northern Ireland, David Sterling noted a no-deal scenario could impose “additional challenges for the police” because of heightened community tensions.

And the head of Northern Ireland’s police service, George Hamilton, has warned that if Brexit results in fixed-frontier customs and security posts on the island of Ireland, it could energize a new generation of violent Irish republicans.

Midweek, three letter bombs apparently posted from the Irish Republic and sent to transport hubs in London were intercepted, adding to concerns of the old sectarian conflicts being reignited over the issue of a hard border.

“Letter bombs posted to London this week were a stark reminder that the peace process is still fragile and the threat posed to it by Brexit cannot be ignored,” The Times newspaper warned.

‘Very unfortunate timing’

The Bloody Sunday massacre of civil rights protesters is one of the deepest wounds of the “Troubles,” the decades-long conflict that was brought to an end with the U.S.-brokered 1998 Good Friday Peace Agreement. The conflict left more than 3,700 people dead as Irish Republican Army (IRA) gunmen battled the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary, as well as Protestant paramilitaries with ties to British intelligence agencies, in their war for a united Ireland.

There are mounting concerns at the highest levels of the British government about how the prosecutors’ decision will play out against the backdrop of Brexit.

“It is an ill wind,” a senior British government official told VOA. “This is very unfortunate timing and we could have done without it, but it is beyond our control,” he added.

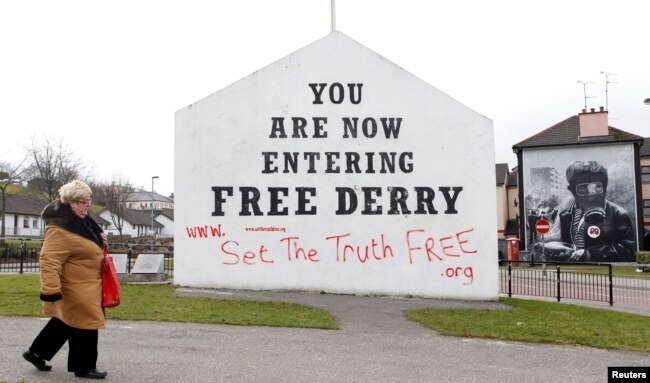

Fears of the reigniting of the “Troubles” have been fanned by a recent explosion in the British province and hijackings in Northern Ireland’s second largest city, Londonderry — which Catholics call Derry, and where the Bloody Sunday massacre took place.

The Bloody Sunday shootings came Jan. 30, 1972, when soldiers from the 1st Parachute Regiment opened fire on civil rights demonstrators in Londonderry’s Bogside district. The demonstrators were protesting internment — the mass arrest and imprisonment without trial of suspected IRA members.

Thirteen people were killed where they stood and a 14th person later died of his wounds. Fourteen other people were injured. The shootings attracted worldwide condemnation and fury in Irish-American communities.

Bloody Sunday investigation

The police inquiry was mounted after a 12-year-long investigation into the killings conducted by Mark Saville, a British judge, which was set up after years of pressure from the victims’ families and supporters in the United States, who dismissed an initial British probe as a whitewash.

Saville concluded that the British soldiers had “lost control” and he detailed a break down in the chain of command, saying the paratroopers fatally shot fleeing civilians and those who tried to aid wounded civilians. The report said the soldiers had concocted lies to defend their actions and, contrary to their claims, none of them had fired in response to attacks by petrol bombers or stone throwers or gunmen. The civilians were not posing any threat, according to the Saville report.

Eighteen ex-paratroopers have been under investigation, and four are thought likely to be charged. Under British regulations, they cannot be named, as yet. One of them, a partly paralyzed 77-year-old, told Britain’s Sunday Telegraphnewspaper that it was a “scandalous betrayal” by successive British governments for allowing the cases to proceed.

“I think it is utter rubbish. But I think we will be charged,” he added.

British army veterans are also criticizing the investigation, saying it is unfair to charge people so long after the event. Former British foreign minister Boris Johnson has said any prosecutions against the veterans will be about politics, not justice.

But relatives of the Bloody Sunday victims have welcomed the possible prosecutions, saying that justice should be done.

“If these soldiers aren’t prosecuted, then the families will be angry, and for good reason,” according to Leo Young, one of the protesters, whose younger brother was killed.